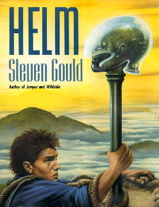

by Steven Gould

Copyright (c) 1998 by Steven Gould.

Artwork Copyright (c) 1998 Jim Burns

All rights reserved. No part of this text or artwork may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without written permission of the Publisher. Exceptions are made for downloading this file to a computer for personal use.

Depending on the circumstance, you should be:

hard as a diamond, flexible as a willow,

smooth-flowing like water, or empty as space."

— Morihei Ueshiba

Prolog

Katsu jin ken - The sword that saves life

They huddled on the floor, shoulder to shoulder, in a rock pocket off the main corridor, moving their heads carefully to avoid banging them on the low roof. A single low-wattage light shone down on dirty hands clutching notes and data screens. Unkempt hair floated above wrinkled brows and sunken cheeks. The fresh, sharp tang of acetic acid from caulk covered cracks mixed with the ever-present smell of sweat, ammonia, and feces.

Those crowded into the corridor outside envied them.

"Is the recorder on?"

"Yes."

"This meeting of the executive committee is in session. Minutes are accepted as filed. The only item on the agenda is the emigration vote."

A minor quake shook the rock slightly and Dr. Herrin stopped talking. Eyes widened and down the corridor somebody started screaming and thrashing around. Dr. Herrin ignored the noise and concentrated on her breathing.

She was sitting seiza, on her shins, composed, her shoulders relaxed, a sharp contrast to the others, who were sitting cross-legged or leaning back against the rough rock walls. Many of those clutched their knees and squeezed their eyes shut.

If the section was holed badly, there wasn’t anything that could be done. There weren’t enough pressure suits to go around. She hoped that the panic in the corridor wouldn’t spread. They had to keep the pathway in the corridor clear so that the emergency squads could get to smaller leaks—the ones that could be repaired.

The month before they’d lost forty-nine men, women, and children when a quake holed a corridor. Vacuum decompression is a violent death and any death was hard to face after so many dead on Earth. Two of the cleanup crew went back to their niches and poisoned themselves.

The quake subsided and the screams down the hall died to violent sobbing.

Dr. Herrin continued.

"There is high confidence in the accuracy of this data?"

Novato, a woman wearing a faded pair of NASA/ESA coveralls, nodded.

Herrin swallowed convulsively, then put her fingertips to her temples and closed her eyes. "Let’s reiterate." She opened her eyes and held up five fingers. "The probe data is more than conclusive. Epsilon Eridani has an Earth-sized planet with a CO2/nitrogen/water vapor atmosphere. The probe has initiated phase one seeding and initial results are excellent—the tailored bacteria are reproducing exponentially and already producing detectable oxygen. And, as you know, these results are twenty-five years old. Based on this data, current estimates indicate that by now, though there are still toxic levels of CO2, the atmosphere is at least ten percent oxygen.

"However, in the hundred and thirty years it will take the ship to reach the system, the bacteria will finish the job. The atmosphere will be fully breathable. Resulting temperatures will be in the earth normal range.

"These are not only encouraging results—they’re optimal."

Stavinoha, a middle-aged man with a shaved head, said, "It’s certainly better than we can get from this solar system." Stavinoha was the last person off the Planet Earth, launching from the Baikonur Cosmodrome in a converted ICBM six weeks after the earth’s mantle was breached at Teheran and, miraculously, snagged at the peak of his ballistic arc by an American Epsilon Class Orbital Tug. Unlike the rest of them, he knew first-hand how bad conditions were on the planet.

The temperatures at earth’s equator hovered around 4 degrees Centigrade. Snowstorms and high altitude dust clouded the planet.

Herrin continued. "There are seven thousand humans on the moon in facilities designed for six hundred. If we don’t do something about reducing the load on our current resources, everyone will die. Given our current status, we might die even if we do reduce the load."

More nods.

"So, we send four thousand in the ship, in cold sleep for one hundred and twenty-five years. However, since it was designed for one thousand, we’ll have to use cargo space as well. This is acceptable because we can’t afford to send all that equipment and supplies away. We need it here to survive on Luna and, eventually, to rehabilitate the earth."

"But they’ll need that equipment!" said the NASA/ESA rep. "It was in the original mission specs!"

Dr. Herrin shook her head. "Yes and no. They’ll need that equipment if they’re to have a high-tech society at that end. It’s been estimated that they won’t need it to survive. It’s a certainty that we do need it here to survive."

She paused to look around the room. "So…our main problem is how to insure they have the highest chances of survival given a low-tech environment." Dr. Herrin looked now at Dr. Guyton, a small man wedged into the corner outside the circle of the executive committee. "I’d like the Focus Committee to summarize the proposal."

Dr. Guyton, an anthropologist, leaned forward and cleared his throat. "We feel that there are three areas we must concentrate on: nutrition, hygiene, and literacy. As you know, the ship already holds a comprehensive and nearly indestructible library. If we can get the colony to retain literacy while surviving the initial colonization effort, we think they can build back to a comparable technology within three hundred years. In the meanwhile, maintaining good hygiene and nutrition will take care of ninety percent of their health problems. Other problems can be taken care of by practical nursing, but, no matter which way you stretch it, they’ll lose people that we could save with our current technology."

He looked around to make sure everyone understood. "What is needed is a strongly enforced code of behavior that will insure good nutrition and hygiene, as well as keep succeeding generations literate.

"Codes of this kind have been a part of every viable culture in our planet’s history, but the most striking example is that of the Talmudic Laws followed by Judaism. Not only do they provide specific instruction on nutrition and hygiene, they also require a Jew to demonstrate literacy as he comes of age."

"We don’t have four thousand Jews on the moon," said Spruill.

"No, of course not. Besides, we need a much more abbreviated version than the Talmud. It contains much that is inapplicable and, frankly, counter-survival under these circumstances. My staff has prepared the basic tenets and we are fleshing them out. We will be ready by the time the ship is."

Bauer, a former congressman from Connecticut, spoke. "What’s to make them follow your code? When they’re scrambling to stay alive on that distant world, what’s to make them take the time to teach it to their children? Are you going to hand it down to them on clay tablets?"

"No." Dr. Guyton exchanged glances with Dr. Herrin. "We propose using the imprinter."

Bauer recoiled. "Jesus Christ!"

Another voice said, "You want to do what?"

There was a moment of chaos as everybody tried to speak at once. It subsided almost immediately, but faces betrayed rage and fear.

Herrin raised her hand and let the silence stretch a bit before she spoke. "Consider carefully, please. Everything depends on what we decide here today." She waited a moment. "Bauer, you object to the imprinter?"

"Our fellow humans destroyed each other because of the imprinter! I’m outraged that there’s even one on the moon! How could this happen?"

Dr. Guyton, the anthropologist, shook his head. "There isn’t an imprinter on the moon . . . but we know how to make them." He leaned forward and held out his hands. "Look, it’s true that the French dropped Mag Bottle Seventy-four on Teheran because the Iranians were using the imprinter to forcibly convert Muslims and non-Muslims to their particular brand of Shiite fundamentalism. But this is an argument against anti-matter as much as it is against the imprinter. We can’t ignore the fact that it could make the difference between life and death for the human race! If we imprint the tenets on the colonists, they’ll adhere to them automatically—with almost religious fervor. This will assure that they pass it on to their children at the earliest age. It’s not as if we’re inducting them into a particular political or religious philosophy.

"And we must also consider the imprinter’s ability to drop a lifetime of experience into the user’s mind. If we were to send loaded imprinters with the crew, we would have a further hedge against failure."

Bauer exploded. "At what cost? You know that information instilled by personality dump is useless without adequate preparatory education. You do that to an ignorant man and you’ll end up with a dangerously confused ignorant man. Besides, no matter whom you choose for the template, there’s no such thing as slant-free information. A political bent will still be imparted!"

The chairman leaned forward. "We are wasting time."

"It’s important!"

"As important as the survival of the human race?" Dr. Herrin turned to the Dr. Guyton. "Is that the extent of the proposal?"

"I just want to point out, again, that this also gets all the anti-matter manufactured to date out of the system. But yes, that’s the extent of the proposal," said the anthropologist.

"Then I call for a vote."

The tally of the main committee was seven in favor, one against.

Dr. Herrin looked at the next page of her clipboard. "Very well. Prepare the catapult. Initiate the ship modifications after the cargo has been removed from the holds and put in stable orbits. We currently don’t have the fuel to bring it down to the moon’s surface, but it’ll be safe up there until we do. As soon as the passenger bags are ready for the launch buckets and the ship is moved to the L-2 point, we set up a catcher crew. As proposed earlier, imprinting will be done after the first stage of cold sleep prep. If they wake up at the other end," she spread her hands and exhaled. "Well, they’ll have religion."

After the vote, Bauer had rested his face in his hands, but he looked up at she said this. "You’re not going to tell them?"

"No," the chairman said.

Bauer’s face turned white. "You must! If you don’t, I will!"

The chairman looked at his furious face and thought about her two daughters, now among five billion humans dead. "Consider how many lives your announcement would end. Panic leading to riots could kill us all."

"Nonsense," said Bauer. "That’s the sort of argument that’s been used to control people through the ages. The only way I’ll keep quiet is if you abandon this plan to use the imprinter."

She placed the palms of her hands together, fingers up, and bowed from the waist. "Then I’m sorry."

He frowned, puzzled. "Sorry? What do you mean? If you think for one minute that an apology will change my—"

She moved then, forward in shikko, samurai knee walking, skimming the floor, really, in the low gravity.

He raised his hands as she closed, uncertain, surprised. She was small woman, unarmed, after all, and he was a large man.

She brushed her right arm against his right wrist and then pivoted, sliding beside him, faster than he could turn to follow. As he tried to twist around, she swept his right arm down with both of her hands, to the floor and back, then the edge of her left hand cut down into the back of his shoulder as she moved behind him, twisting her hips. He bent over abruptly, face down, his own arm a crowbar levering his torso down.

She reached across the back of his head with her right hand, slid it down across the side of his face, and reached under, to cup his chin. Then she pulled, twisting her hips and shoulder back in one abrupt movement.

Bauer stared up at her, his torso still facing down, his neck twisted one hundred and eighty degrees.

Everyone in the small chamber heard his spine snap.

Dr. Herrin laid him on his back, carefully, folding his hands across his chest, then backed away, still on her knees. She bowed again, to the body.

The rest of the committee stared, shocked, shifting their eyes between her and Bauer’s lifeless form.

When Dr. Herrin finally spoke, her voice was calm. "The vote on emigration stands. I depend on you, Dr. Guyton, to handle the imprinting procedure with appropriate candor. As to my behavior in this incident," she nodded toward Bauer’s body, "I tender my immediate resignation."

She slumped then, her hands folded on her lap, her eyes downcast. In a quiet, empty voice she said, "I have betrayed my training. If the committee decides I should live, I would like to go with the colony."

Chapter One

shoshin: beginner’s mind

First there was the cyanophyta, the blue-green algae, a hundred different kinds, tailored to float at various strata of the atmosphere, to lie in puddles of water, to infest the shallow seas. They were injected into the upper atmosphere in ablative capsules that exploded when they’d sloughed off enough heat and velocity and floated on the winds.

Some varieties went extinct, never finding their needed habitat, but others thrived, harvesting carbon out of the all too plentiful CO2 and releasing oxygen, and, at an exponential rate, reproducing.

Next, when the temperatures began to subside, came the lichens, desert, arctic, jungle, temperate—tiny filaments of fungus surrounding algae cells. These soredium fell like fine ash, scattered through the atmosphere to fall gently to the rocky surface.

In some regions the fungus couldn’t attach to the rock, or there wasn’t enough water, or sunlight, or there was too high a concentration of heavy metals, or it was too hot, or too cold, or any of a hundred other versions of just not right. But elsewhere, in the cracks, in drifts of crumbling rock, and in basins of dust, they thrived, the fungal layers absorbing minerals and water while the algae did their photosynthetic magic with CO2 and sunlight.

Right behind the lichens came the decomposers, bacteria and fungi critical to the breakdown of biological material. The fungal filaments of lichen found tiny cracks and flaked off bit after bit of rock. And as parts of the lichen aged, or conditions changed, they died, and the decomposers went to work, mixing with the dust and water—a simple sort of topsoil was born.

Later, the grasses, clovers, and other complex ground covers came, along with simple aquatic plants, and desmids and other freshwater plant plankton, more ablative capsules put in deliberately decaying orbits and entering the atmosphere like clockwork—ten, twenty, thirty, forty, fifty years after the lichens. Freeze dried bundles of bacteria, fungus, and seed encased in nutrient pellets fell like rain to die, flourish, or lie in wait.

These early arrivals were limited to those varieties that could self pollinate, or spread asexually, by budding and branching. Their root systems were, for the most part, shallow. Except for pockets and basins where natural forces had concentrated dust and rubble before the arrival of life, the new soil was thin and tenuous, easily disturbed by wind and water.

The first insects arrived by parachute, in capsules targeted on the highest concentrations of reflected chlorophyll spectra. While the capsules still floated high above the ground, small openings ejected newly revived impregnated queens of the honey bee, the Asian carpenter bee, and the bumble bee, as well as fireflies, caddis flies, non-biting midges, cockroaches and lac bugs. Closer to the ground, the capsules scattered earthworms, butterfly larva, crane fly larva, and crickets.

Specialized capsules delivered animal plankton—rotifers, copepods, and cladocerans—to bodies of water large enough to detect from orbit.

The next spring came the predators: praying mantis, ladybugs, ground beetles and other insects. Spiders included orb weavers, trapdoor, tarantula, jumping, and wolf. The capsules scattered them wide, ejected kilometers above the surface in gossamer packets of protein webbing that slowed their fall. On the ground, the webbing broke down, oxidized within minutes of creation, freeing the spiders and insects to hunt and eat.

To the waters came protozoa, minute crustaceans, hydras, dragonfly larvae, diving beetles, and other aquatic insect predators.

The vertebrates came with man.

In Agatsu's more turbulent past, a freak crack had formed in brittle crust and iron-rich magma had thrust its way up a narrow fissure in the sea bed, trying to reach the lesser pressures above. Fifty million years later, after wind and water had done their work with the surrounding shale, the hardened rock raked the sky, a dagger of rusty granite sixty meters across at the base and over three hundred meters tall. When the sun neared its zenith, the tip of the spire would flash brightly, reflecting light that could be seen clearly over five kilometers away.

They called it the Needle, and Guide Dulan de Laal had forbidden any man, woman, or child, on pain of Dulan's wrath, to climb it.

Lit by the planet’s ring the Needle was an ivory tower against a dark sky. It sprang abruptly from the forested side of a low hill, and climbed sharply into the night sky.

Three kilometers from the Needle, below the massive structure of Laal Station, the town Brandon-on-the-Falls was brightly lit. It was the last day of the fall harvest, and Festival had begun. The Station was also ablaze with lamp light, and a steady stream of traffic curved down the mountain road from the fort to the town.

Leland de Laal wiped sweat from his brow as he watched the castle and the town begin the Festival. He smiled for a moment, picturing his three older brothers dancing and drinking in the town. Even little Lillian would be there under the watchful guidance of Guide Bridgett. And where would Father be? Oh, yes—the judging and blessing—spring ale, fruit, and grain. Doubtless, he'd drafted Guide Malcom to help.

The rope was biting into his chest. Leland decided he'd rested enough and shifted on the tiny ledge, bringing the rope over his head. He edged his way over to the six inch vertical crack he'd chosen earlier and begin working up it, jamming his boots sideways and reaching his hands back as far as they could go. Centimeter by centimeter, he climbed his way up the rock face.

Prohibitions or not, he was already three-quarters up the Needle.

His grip began slipping from moisture on his fingertips so, every time he pulled one hand from the crack, he'd wipe his fingers across his shirt. This left dark streaks across the white cloth—blood from abraded skin.

Step up—set the foot. Free a hand—wipe it—reach higher. Repeat as needed. Don't waste any strength on moans or grimaces. Ignore the grinding of rough stone into raw fingertips. Just climb.

Fifty meters from the top he paused. The wind pulled at him, a gentle breeze that cooled his sweat soaked clothes and threatened to pluck him from his precarious hand holds. He freed one hand and took another iron spike from his belt. Carefully, he wedged it in a small crack on the right, then took up the hammer hanging from his neck on a lanyard.

His aching arm muscles twitched as he swung at the spike, causing him to strike the head off-center. He cursed as the spike flew past his right shoulder and fell into the dark. The sound of it bouncing off the face of the Needle far below came to him once, and then nothing.

Tiredly, he groped for another spike and his hand closed on two sticking out of the loops in his belt. Two? He groped further. Only two out of the thirty spikes he'd started with remained. For the twentieth time since he'd left the trees below, he considered quitting and going back down.

He leaned out and craned his head back, gripping the crack tightly. The tip of the needle floated above, ethereal in the moonlight. So close!

With far greater care, he placed and drove in the next to last spike.

Hanging from the spike in the rope and plank chair, he collapsed against the rock face and let his muscles shake.

Time passed and the wind died softly to the barest sigh. Leland's muscles began to chill and stiffen from inaction. He forced himself to eat cheese and bread from his belt pouch, chewing automatically after muttering the categories. He was mildly surprised when his blindly searching fingers came out of the pouch empty.

In the distance, the town and station still swarmed with activity as the Festival neared its peak. On the flat plain between the town baths and the castle moat, a bonfire blazed and three rings of dancers circled the flames while the castle band and town symphony played. Leland could just make out the High Seat where his father should be presiding and, if he held very still, the music floated gently to him.

Enough, sluggard. He eased back to the crack, almost crying when the dried blood on his fingers cracked open again. His muscles screamed protest as he recovered the plank chair and began climbing again.

Five meters from the top, the crack narrowed to a hairline fracture too fine even for his last spike. There were no hand or foot holds within reach.

So close? The Needle was less than two meters thick where Leland perched and it narrowed rapidly up to the narrow, meter-wide circle that was the Needle's point. Only another two meters and I could get my arms around it. He started to slump against the rock, disappointed.

Arms around it . . . why not?

The trick was going to be tying a knot with one hand.

Leland reached behind him for the rope that hung coiled from the back of his belt. It was his way out, a length of rope twice sufficient to lower him from spike to spike. He stuck his head through the coil and used his teeth and free hand to untie the knot that held it together. Then, a free end in his mouth, he pulled the last spike from his belt and tried for several frustrating minutes to tie a knot around it. By the time he'd succeeded, his legs and arms were trembling and he'd had to switch his grip several times to wipe off slippery blood.

Lowering the rope slowly, he began swinging the spike from side to side, banging it against the stone first to one side, then the other. He played out the line as the speed increased, gradually wrapping farther and farther around the circumference of the Needle as the period became larger and larger. As the rope's length neared what was needed to circle the Needle's diameter, the violence of Leland's swinging threatened to pull him from his perch. Just as he felt sure he could hold no longer, the rope completed its farthest swing and slapped across the back of Leland's leg. He flipped the lower part of his leg up, leaving him perched dangerously with one foot and one hand wedged in the crack, but also with the rope stretching from his right hand all the way around the Needle to end up hanging from the back of his left knee.

Sweat trickled into Leland's eyes. His heart pounded heavily in time to quick, deep breaths. Still holding tightly to the rope, he worked his right hand back to the crack and wedged it, rope and all, above his other hand. Then he released his left hand and groped for the rope trapped in the crook of his knee. When he had it in hand, he was able to return the left foot to the crack.

He flipped at the end in his left hand, alternately pulling and flipping the rope, getting it to climb the sloping rock until it was slightly above him on the other side of the Needle. Then, maintaining the tension as best he could, he moved his left hand as far out to the side as he could and pulled his right hand from the crack.

His heart seemed to stop as he leaned backwards, then thudded to clamorous life as the rope, one end in each hand, held him, logger style, to the Needle.

So far, so good. Leland walked up the crack, maintaining tension on the rope to keep him from falling away from the face. When he reached the top of the crack, he took up the tension in the line and flipped it higher on the far side. This entailed leaning forward quickly, flipping the rope, and then taking up the tension again just this side of disaster. Luck was with him for the rope found some projection higher on the other side and caught. Leland took his right foot out of the crack and planted it on the rough, sloping granite.

Up he went, not daring to pause, for his arms were trembling and his nerve was almost gone. Soon it became more of a scramble, as the Needle narrowed to a mere meter and a half. Then, foot and hand holds appeared near the top and with a last desperate lunge he was over the edge and hugging the shining metal post that cradled the Glass Helm.

Leland trembled, shook. His legs and arms cramped and his eyes stared vacantly at the Agatsu's ring. The rope and assorted climbing paraphernalia draped over the sharp edge and dangled, like his feet, over the abyss. At first he was just drained, empty of all feeling. Even the cramping in his arms and legs seemed remote, like they belonged to someone else. He concentrated on just getting air into heaving lungs.

I won't spoil this minute by throwing up!

Then, along with biting pain and nausea, the exhilaration flooded into his body.

Not bloody bad for the bookworm! He struggled to sit, still hugging the ten-centimeter thick post where it sprang from the rock. This movement brought his head level with the Glass Helm.

I am looking at a legend, Leland thought, awestruck. By the Founders, it's beautiful!

The gleaming metal post terminated in a stylistic model of a human head, full scale, with mere suggestions of facial features represented by smooth depressions and curves. With crystalline grace the Glass Helm crowned the metal head, a brilliant cascade of reflected moonlight and odd patterns buried deep within the transparent matrix.

When was the last time a human looked at this? Did the founders put it here with their flying cars? Does the legend come from them?

Leland reached out and gently ran a fingertip over the surface. Smooth, so very smooth. "What . . . !"

Blood from his torn finger had seeped onto the glass. Almost immediately, the Helm began to change. Minute flashes of phosphorescence seemed to run along the patterns (wires?) buried deep in the glass. From cold immobility to warm, barely perceptible pulsing, the Helm seemed to come to life. There was a visible movement as the part of the Helm that gripped the metal head's temples spread a full centimeter. Leland touched the Helm again, and it moved freely, no longer bound to the post. He shrank back from the Helm as far as he could without actually going over the edge or releasing his grip on the post.

How many have made this climb and stopped at this point? He squeezed his free hand into a fist and winced at the pain this caused. Father be damned, fear be damned, and Founders be damned! Not me!

He stood (because it seemed right) and lifted the Helm from its stand. Then leaning firmly against the post to steady himself, he lowered the Glass Helm onto his head.

Guide Dulan de Laal, Steward of Laal, Sentinel of the Eastern Border, and Principal of the Council of Noramland, was relatively content. The summer's harvest had provided a large trading surplus above and beyond satisfying the categories, and the sugar in this year's grapes was very high, meaning good wine by spring—even better for the trading. The Festival was winding down for the night, though it had two more days to go, and he and Guide Malcom de Toshiko, Steward of Pree, were listening to the town symphony play a requiem for the day.

"A good Festival, Dulan. You treat me like this every time I visit and you'll have a permanent house guest." He looked sideways at Guide Dulan, smiling.

Dulan snorted and shook the huge mane of silver hair that closely framed his face. "Do it, dammit. What keeps you in that drafty hall of yours? Kevin is holding it quite well."

Malcom sighed. "And when I'm there, we fight tooth and nail. Don't think I'm not tempted. It's been two years since Mary died and I still can't walk into any room in the place without expecting her to be there."

Dulan nodded at his old friend's confession. "I know. It's the same for me with Lil, and she's been gone these seven years. It's almost heartbreaking to look at Lillian and see her mother's eyes looking back at me." He lifted a pitcher of ale from the table beside him and freshened both their tankards with a muttered grain. "Perhaps we should remarry?"

"Ha! And inflict our ghosts on innocent women? Better to take a harmless tumble when the need becomes too great. Like your sons, eh?" He pointed to the edge of the green where Dexter, Dulan's second oldest son was walking into the dark with a town girl.

Dulan frowned, then smiled slowly. "I saw Dillan and Anthony vanish likewise, earlier. They better be careful ... if the wrong lover got hold of them. Well, even Cotswold's fingers reach this far."

Malcom frowned. "Surely you've trained them against that?"

"Oh, of course. Just an old man's fears."

"And even little Leland, eh?" said Malcom sipping from his tankard.

"Doubt it. He's old enough—fifteen? No, by the Founders, sixteen, and seventeen next month. Where does the time go? But, Leland is a strange one—more likely in the library wasting candles."

"Dulan!"

"All right. Not wasting. And I wish his brothers had half the time for the scholarship. But there's the other side, too. He's timid—doesn't get out enough. Well, he did work in the fields this harvest—like a dog. He does pursue whatever interests him with a passion. But he never stands up for himself."

"Oh? Is he beaten regularly?"

"No, he backs away when there's any sort of confrontation."

Malcom smiled. "Maybe he knows more about fighting than you think."

Dulan snorted. "I doubt it. Anyway, it makes him look weak, and that only makes him a more likely target." He stretched his arms and looked up at Agatsu’s ring, then looked carefully around for listeners. "My agents in Cotswold are nervous. The people are hungry and the Customs are being twisted. Siegfried is directing their attention this way. This may lead to a confrontation that Leland cannot avoid."

"When?"

"Well, next harvest at the earliest. Even as poor a farmer as Siegfried Montrose was able to harvest enough this season for the coming winter, though he's hardly filled the categories. The rains have never been better. But, next year will be much dryer, and Cotswold doesn't have the watershed we do. They'll probably strike after we've done the work of getting in the harvest."

"Risky, that. Then you're stocked for a siege and they won't have supplies to outlast you." Malcom looked thoughtful. "Laal Station has never been taken, either by storm, or by siege."

"True—but how long has it been since someone tried? Eighty years. Our population has doubled since then—they won't all fit in the Station now. Even half would cause problems with sanitation." Both men touched their foreheads automatically.

"Enlarge the Station?"

"Well, we could go into the mountain, I suppose. But the manpower...." He should his head. "Doing it by next autumn would require skipping next year's harvest."

Malcom frowned. "Then what will you do?"

Dulan tapped the gray, curly hair that covered his temples. "I've a few ideas," he said with a surprisingly boyish grin. "I've a few ideas."

The music changed to a waltz and several of the crowd came forward to dance. Malcom stood and asked Guide Bridgett onto the "floor." After entrusting Lillian to Dulan's care, she accepted.

Little Lillian crawled up in her father's lap and promptly fell asleep. Dulan cradled her and smiled, stroking her hair and watching the swirling dancers on the grass. He was as surprised as any when the music died discordantly, one instrument at a time, ending with a lonely flute note that hung in the air leaving a phrase achingly incomplete.

Dulan stood and carefully placed the still sleeping Lillian on his chair. Then he looked over the heads of the crowd, trying to determine the cause of the interruption.

There must have been fifteen hundred people in the clearing, fully ten percent of Laal's population. The muted roar of that many people talking, wondering aloud, and supposing filled the air. Then Dulan heard a shout from the forest side of the clearing, near where the musicians sat, and he saw the crowd at that edge split and spread apart, forming a path leading in the direction of Guide Dulan's seat. The Steward frowned and stood on tiptoe, but he couldn't see what the crowd made way for. And he was damned if he'd clamber onto a chair like a child to see, so he waited stoically for whatever was coming.

Moments later, the crowd in front of the high seat parted. At first he didn't recognize the figure that walked toward him. The great bonfire had died to embers so torches and ringlight were all that lit the festival field. The Steward could see that the man was small and walked stiffly, almost unnaturally. Then the figure stepped nearer one of the torches and Dulan caught a glimpse of a blood streaked shirt and a coiled rope draped awkwardly across one shoulder. Another step closer to the torch and the figure's head seemed to catch fire as the gleaming headgear he wore caught the torch light and threw it at Dulan.

He staggered as if hit. The Helm! His hands went automatically to his own temples, to the crescents hidden beneath his hair. Then, and only then, did he recognize his youngest son, standing rigidly before him, swaying slightly, staring fixedly at Dulan with a face empty of expression.

Dulan stepped forward. "What have you done?" He shouted the question with anguish in his voice. Those nearby stared in shock, for Guide Dulan had last been heard to raise his voice the day his wife had died. His calm was legendary.

Leland blinked, then slowly shook his head as if befuddled. Slowly, clumsily, he raised his arms and lifted the Glass Helm from his head. As he did, a tremor passed through his body and he collapsed, full length across the trampled grass. The Glass Helm bounced once on the ground and rolled to a stop at his father's feet.

Dulan's question went unanswered.

For three days Leland lay unconscious in the confines of his room, attended always by a one of the Laals or Guide Malcom. The servants' gossip was full of the tale of Leland's climb. By the first evening, the exact extent of Leland's injuries was known by the youngest kitchener, from his torn and bloody fingers to the half-circle burns on his temples, where the Glass Helm had marked him.

"I've never seen the Guide look like this. I don't think he's slept in two days—he just sits in his study and stares out at the mountains," Captain Koss told Bartholomew, the Kitchener Manager. "Even at the battle of Atten Falls, with Noramland's army in pieces and the Rootless pouring across the river, he exuded confidence. You'd have thought it was a picnic. It scares me to see him like this."

Bartholomew smiled at the thought of Captain Koss scared of anything, but said, "As one ages, cares aren't handled as well."

From Dulan’s study window, the Needle was a finger pointed at the sky rising from behind a green hill. He stared unseeingly at it and brooded.

Damn it all to hell, he thought. Two decades of charging wasted! Why, oh why, Leland? Dillan was going to be ready soon, I could feel it. But not now, not for twenty more years, if the house survives that long . If civilization lasts that long!

Leland, oh Leland. You were a treasure to me. A child of love without worry of utility or station. You were there for me to treasure as a child and a son—not a weapon I must hone, a tool I must shape.

Dulan grieved. He grieved for himself. He grieved for Dillan, his eldest. He grieved for Lil his late wife. But most of all, he grieved for Leland.

I hope you can survive the forging!

There was also much speculation as to the nature of the Glass Helm. Guide Dulan himself placed it on a helmet stand beside Leland's bed, where it sat lifeless, lusterless and cloudy. He bound it in place with wire and sealed it with wax and his signet.

"Undoubtedly magic," Sven the junior kitchener assured his peers. "How else would the weakling have made it up the Needle if not assisted by sorcery?"

"Fah! He's strange, but he's no weakling. He worked the full harvest in the fields, and it was no sham. I saw him sweat. You have magic on the brain."

"Sure I do. That's why he lies in a trance."

"Listen, twit. If I'd climbed the Needle, though I doubt I could, I might sleep for three days myself!"

Sven laughed harshly. "And the exertion would leave the demon brands on your temples, too?"

There was no answer to that.

On the fourth day, the patient opened his eyes and stared blankly at Guide Malcom. "Uncle Malcom?", he croaked, intelligence returning to his eyes.

"Yes, Leland. Here, drink some of this."

Leland tasted it and made a face, then he saw the Helm on the table beside him. His eyes widened. "It wasn't a dream, was it?"

"No," said Guide Malcom, "definitely not."

A haunted look came to Leland's eyes. "It put something in my head." He touched his hair gingerly.

"What sort of something?" Malcom asked.

The haunted look became one of frustration and pain, "I don't know! I can feel it in there, but it's all dark. I can't get a hold of it."

"Don't try. Don't let it bother you. Don't even try to think. Drink."

After the boy sipped half of the offered medicine, Malcom went to the door and sent a servant for the Steward. Scant seconds passed before he arrived.

"So you're going to live, eh?" Dulan's first words as he came into the room were spoken forcefully, without a hint of kindness. Leland's tentative smile died before it touched his lips and his face froze to stony immobility.

Dulan went on. "You have a month to recover your health. One month—no more. And then, my fine climber of rock, you're going to wish you'd never been higher than your head. When I'm done with you, you'll probably wish you'd never been born!"